envisioning an inhabitable, responsive space

The Vancouver residential tower is often associated with two characteristics: floor-to-ceiling glazing, and slab-extended balconies with impressive views.

However, the balcony has not always been a part of Vancouver’s vernacular. Prior to the 1960s, most multi-family residential developments did not have balconies because they counted against a building’s total floor area. This changed in 1964, when the City of Vancouver introduced a balcony exemption to encourage developers to provide additional open space for apartment dwellers.

Today, in contemporary real estate, the apartment balcony is a strange duality: balconies are highly desirable for buyers, yet they often end up being underutilized space. As stated by Toronto architect Rodolphe el-Khoury, the “balcony may indeed be the architectural equivalent of the NordicTrack machine. You buy it because you want to see yourself using it, but seldom do.”

Balcony use may be higher in Vancouver than Toronto, however. Local marketing companies vehemently believe that apartment owners use their balconies, especially when the balcony is an extension of the living space.

For the residential architect, the balcony offers one of the few apartment spaces left for formal experimentation. Apartment layouts are often optimized for the market’s aesthetic expectations, and economic constraints often determine most of an apartment’s design before the project has even begun. Balconies, however, are still open for architectural expression, and have numerous attributes to explore. The balcony can be a design complement, a connector, or even an opposite. And as an intermediate space, the balcony is locked in a threshold between public and private, and between inside and outside.

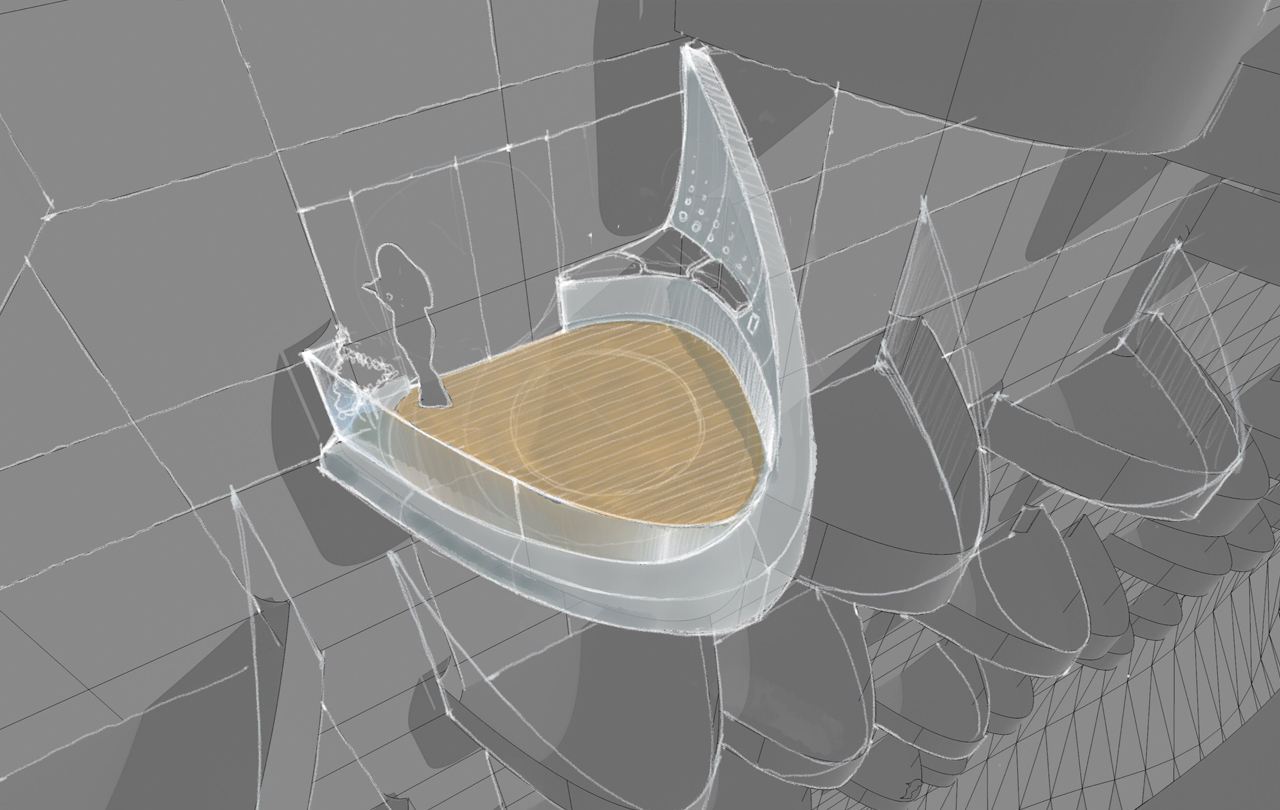

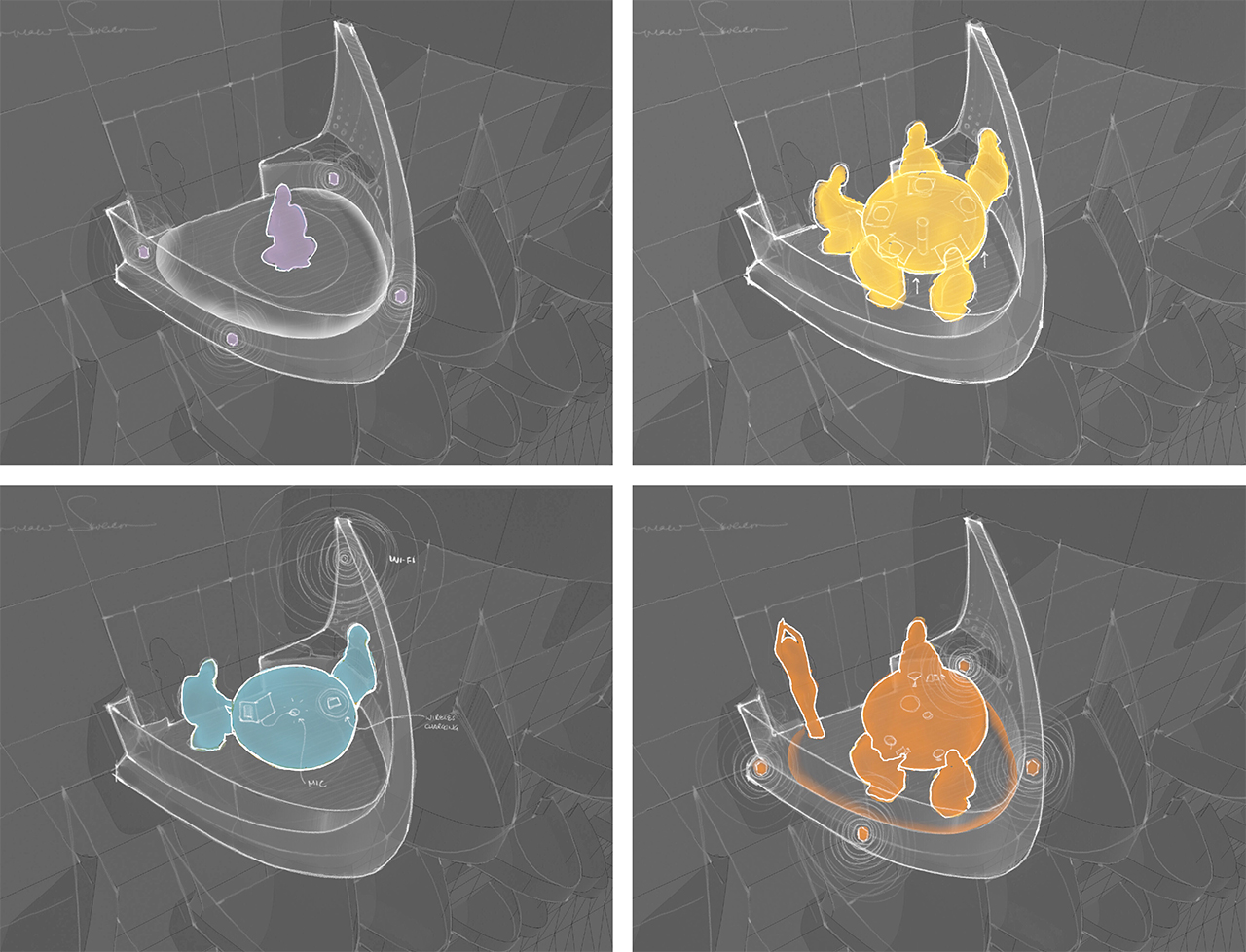

The design for the Oakridge “Sanctuary” facilitates a flexible range of activities, including sitting, lounging, dining and meditation. Typically, designing for programmatic flexibility results in a static, rectilinear space. However, the intention for the Sanctuary was to create a space that could physically change throughout the day and adapt to changing scenarios. As a result, the Sanctuary is highly-articulated, ergonomic, and responsive – the space enhances the user’s experience by existing at a scale in-between architecture and industrial design. A useful precedent for the project was the business class airplane seat, in which the passenger has access to a series of components at arm’s length.

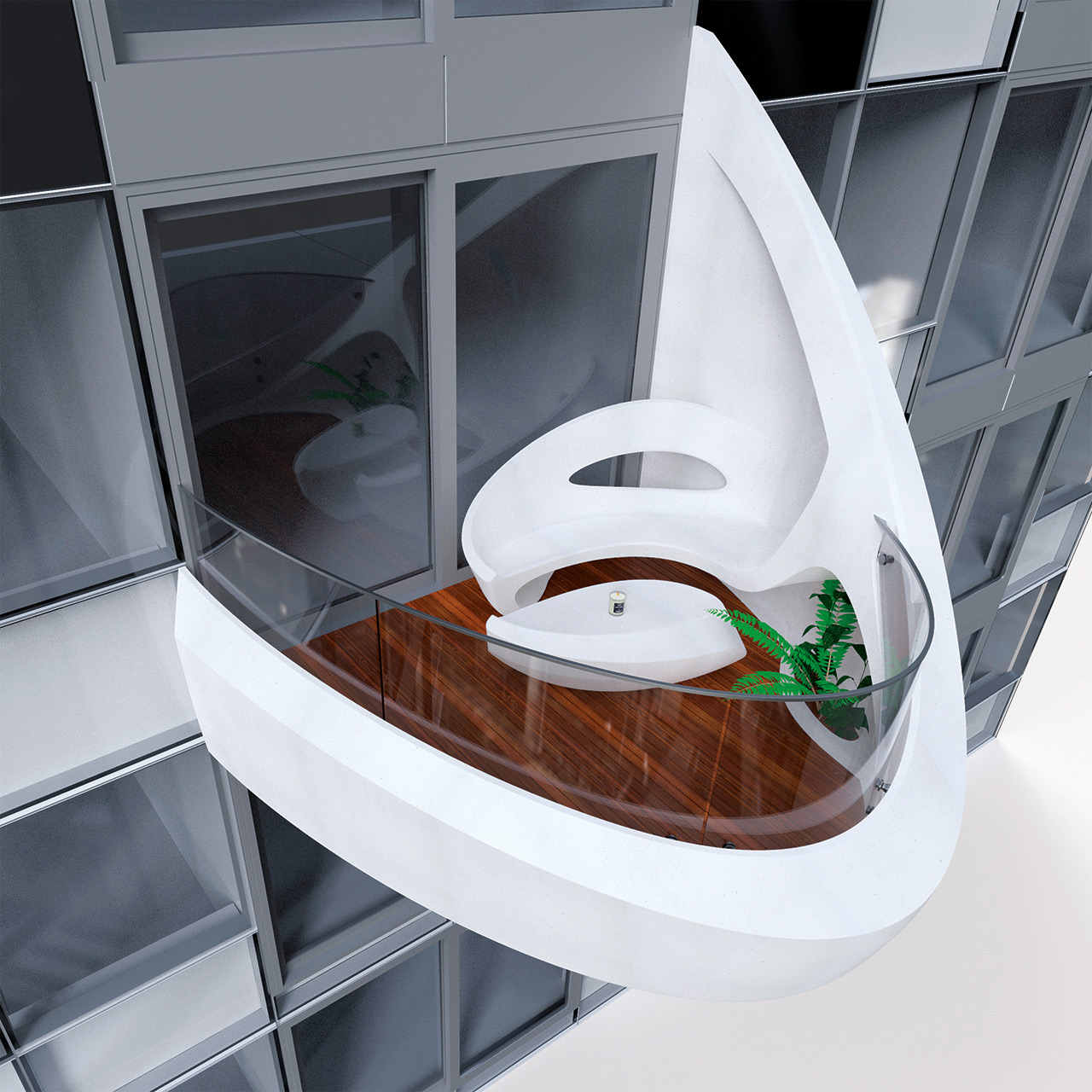

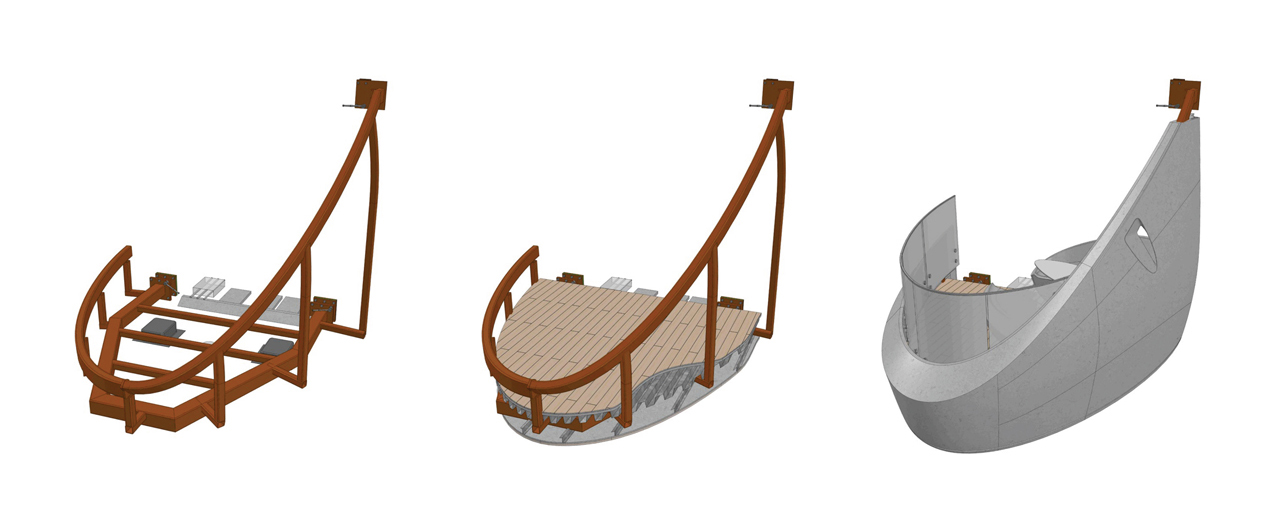

Appropriately, the project team collaborated with industrial design office Form3 to shape the many formal possibilities for the Sanctuary. Form3 created full-scale cardboard prototypes of the floating seating and conducted testing for seating arrangements of one, two and three people. In the final design, the floating seating and ottoman combine into a singular form for one person; to accommodate multiple users, the ottoman can slide away to act as moveable seating, and reveal a small table that is stored inside it. Materially, the form creates privacy with a concrete, cellular wall; its organic form gradually lowers and transitions to glass, extending the space outwards and revealing views of the public park below. Both the seating and flooring are heated by an integrally radiant heating system. Other features include LED perimeter mood lighting, alcove and ceiling lighting, multimedia audio system and speakers, electrical outlets and an iPhone dock. There is even a small planter integrated into the floor.

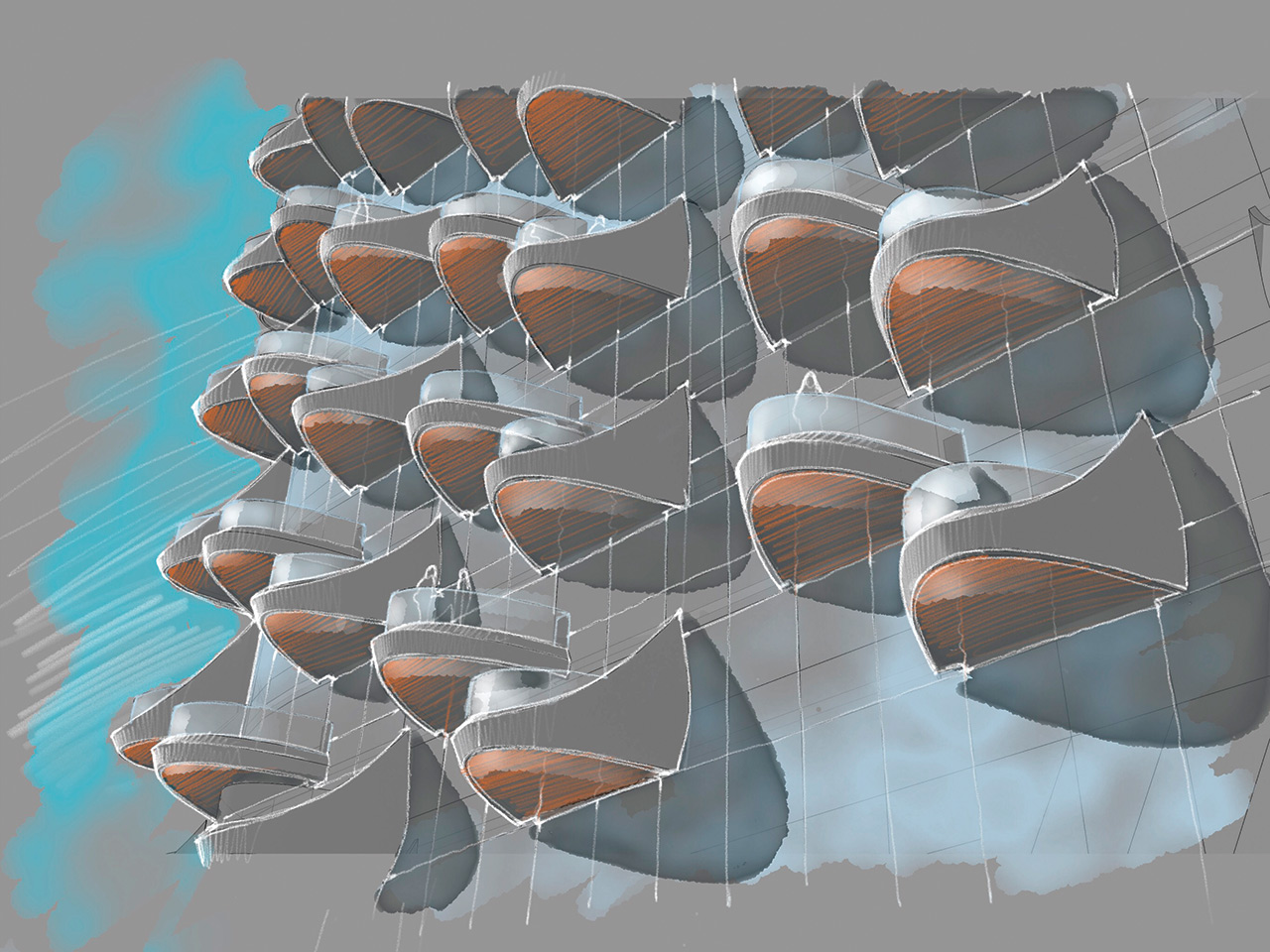

As a building element, the balcony has an auxiliary character that gives it a degree of neutrality and independence from the rest of the architecture. The Sanctuary was considered in similar conceptual terms. When viewed from the architectural exterior, the Sanctuary was intended to look like an “applied object” that has been attached to the building’s glass curtain wall.

The Sanctuary is the latest in a series of contemporary explorations into how the balcony can contribute more to residential architecture. As stated by Sou Fujimoto, “[a]s cities become more and more dense, the ground level is under enormous pressure to provide many things to many people.” In response to these conditions, Fujimoto’s L’Arbre Blanc makes the balcony the dominant formal element of his tower in Montpellier, France. In Milan, Stefano Boeri’s Bosco Verticale places 800 trees and 15,000 plants on the tower’s balconies in a “vertical densification of nature.” Together with the Sanctuary, these projects offer contemporary conceptions of the residential balcony – how it can become a more dynamic architectural expression and a more meaningful part of an inhabitant’s daily life.